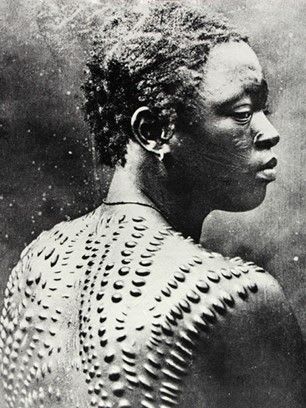

While tattooing has historically been a popular way of permanently marking the skin amongst people groups with lighter skin, scarification is a practice that is prevalent amongst Africans and even Australian Aboriginal groups. The scars are made by cutting or branding the skin, sometimes forming raised lumps (keloids) which are hard to miss on dark skin. The keloids may be arranged in intricate patterns over large areas of skin.

Scarification in Africa usually involves a great deal of technique. Cutting along the skin with metals, pieces of glass or stone tools leaves flat scars, while rounded scars are made by raising portions of skin with a thorn or hook then slicing it across with a blade. Effects can then be created by rubbing the wound with ink, filling it with clay, ash or even gunpowder to form keloids. The wounds may also be forced to remain open by pulling either side of the skin tight to form a permanent gouged scar.

The scars are often primarily used for beautification, however they may also have special ritual purposes or be a form of identification. Moreso, the painfulness of the process may be used to test an individual’s ability to withstand pain and, consequently, readiness for the harsh realities of adulthood.

In this article, we will be looking into the methods and significance of scarification practices across some African ethnic groups.

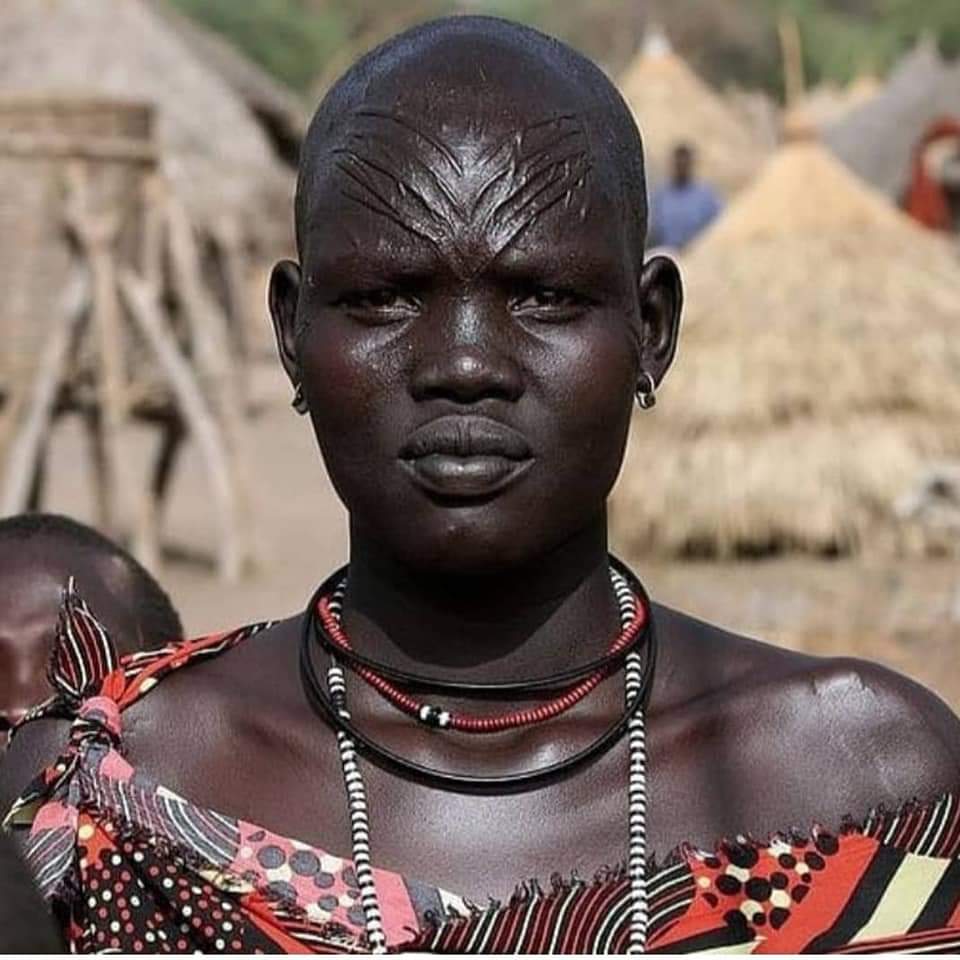

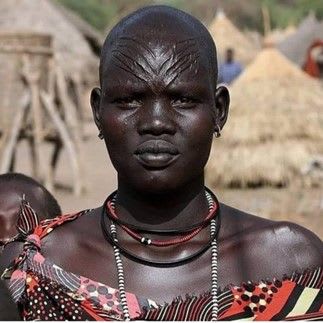

Dinka (South Sudan)

Dinka people receive scars on their foreheads as a way of identifying with their clans. Though there are varying patterns according to the person’s clan, a popular kind is a fan-shaped scar with jagged edges. There may also be scars on other parts of the body to symbolize good health fertility in women and strength in men. The scarification is often done as a rite of passage into manhood for boys; those who show no emotion while they are being scarred are believed to be worthier members of the group, while those who cry, wince or show any indication they are in pain are looked down on.

Nuba (Sudan)

Nuba girls traditionally get marked on their forehead, chest and abdomen at the start of puberty. Then when they begin their first menstrual period, they get marked under the breasts. The final phase of scarring occurs after the weaning of their first child, a set of scars running across the sternum, back, buttocks, neck and legs. While these scars indicate the stage of life the Nuba women are in, they are also seen as a mark of a beauty.

Additionally, the Nuba people use scars as a form of preventative medicine. Scars above the eyes are believed to improve eyesight, those on the temples are believed to relieve headaches, while a four-pointed star near the liver is said to protect against hepatitis.

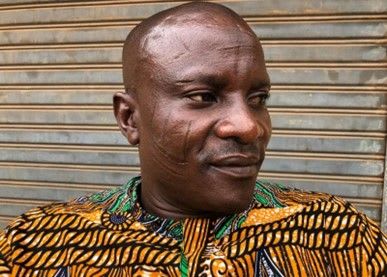

Yoruba (Nigeria)

The Yoruba peoples of South-West Nigeria use different styles of facial scarring called tribal marks to identify with their various ethnic subgroups or even families. For example, indigenes from Owu, a historical city in Abeokuta, bear a set of three vertical lines and three horizontal lines called ‘Abaja Olowu’ on each cheek. There are several other styles like Soju, Pele and so on, and some are milder than others. The marks are usually made during infancy or early childhood. In the past, special marks given in adulthood could indicate a certain social status. The practice is largely outdated due to associated stigma, so it is more common to find Yorubas born at least before 1980 with tribal marks.

Other Nigerian ethnic groups, like the Tiv, Ekoi and Hausa, also practice scarification. Interestingly, the Ekoi (also Ejagham) people of South-South Nigeria believe that their scars will serve as currency on their way to the afterlife.

Houeda (Benin Republic)

The Houeda people believe that the scarification of children establishes a connection between them and their ancestors. After children receive scars on their faces, they are given new names and have their heads shaved before they are taken to an oracle who helps them communicate with their forefathers.

Suri and Mursi (Ethiopia)

Suri men scar their bodies to indicate that they have killed someone from the enemy tribe. A scar in the shape of a horseshoe on the right arm indicates a male victim, while one on the left arm indicates a female victim.

On the other hand, the Mursi, neighbours of the Suri, primarily use scarification for aesthetic reasons. Swirling dotted patterns on the bodies of both men and women are used to attract the opposite gender and heighten the tactile experience of sexual intercourse.

Luba (DR Congo)

The Luba people of the Democratic Republic of Congo see scarification, as well as hairstyling, as a way of marking one’s history and their societal status. Since one’s memory grows with age, more details are added in the form of new scars. Thus, the skin is likened to a book which is to be written on and read by others. Additionally, for Luba women, the extent of scarring is seen as an indication of their ability to withstand the pain of childbirth.

Understandably, concerns have been raised about the safety of scarification practices in Africa. The methods used are not exactly sanitary and could pose great health risks to those who are marked, especially when inadequate care is given to the healing process. This has led to their dwindling popularity and acceptance.

Furthermore, many argue that there is no use for scarification anymore. Historically, tribal marks were sometimes used to instantly distinguish between warring groups or to trace the ethnic group of lost people and slave captives. Now, they are widely seen as unnecessary and even unattractive.

Still, some African groups insist that the scars are part of what completes their status as members of their communities and have thus refused to let go of the practice.

Oyindamola Depo Oyedokun

Oyindamola Depo Oyedokun is an avid reader and lover of knowledge, of most kinds. When she's not reading random stuff on the internet, you'll find her putting pen to paper, or finger to keyboard.

follow me :

Leave a Comment

Sign in or become a Africa Rebirth. Unearthing Africa’s Past. Empowering Its Future member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.