The brutal and unrelenting exploitation of Africa’s natural resources to satisfy insatiable global consumption demands since colonial times has hardly changed. If anything, it is incontrovertible colonialism has undergone fundamental permutations in the contemporary: neocolonialism [embodied in globalized neoliberal capitalism].

African people are perpetually mired in material realities marked with untold immiseration – but with closer analysis, everything points to colonial continuities through neocolonialism.

Neocolonialism, abetted through the collaboration of African [corrupt] leaders, is responsible for the unbridled exploitation of natural resources while local populations have nothing to count for it, and Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea, Sudan, Angola, among other resource-rich nations provide apt case studies.

There is a plethora of literature dissecting this regrettable reality, with the conventional tropes that include “the resource curse”, “the new scramble”, and the “paradox of plenty”. And with the entrance of China in Africa’s energy sector as the alternative to Western hegemonic and global supremacy, such neocolonial narratives require more nuanced approaches.

Colonial Profit-Seeking Primitive Accumulation and the Neocolonialism Today

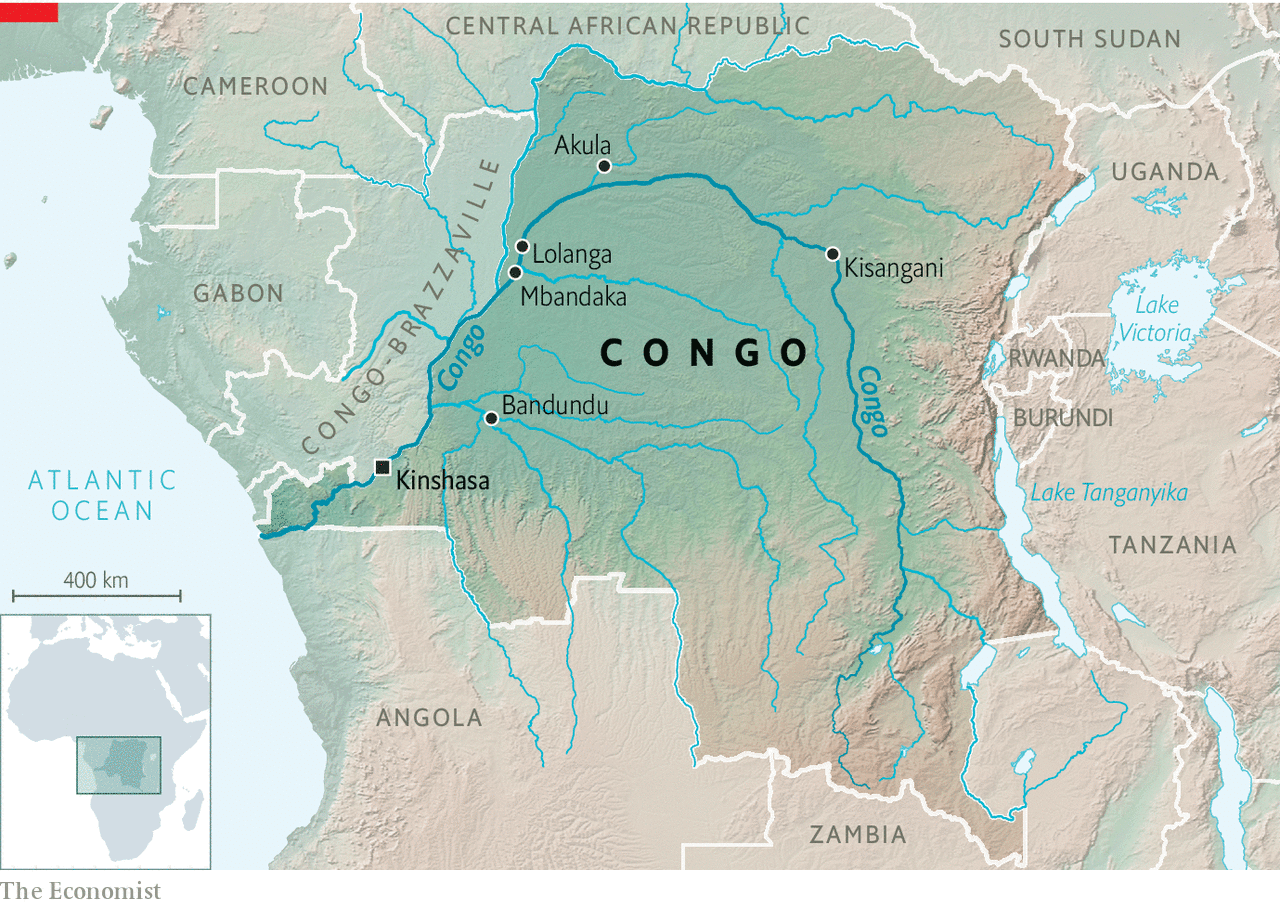

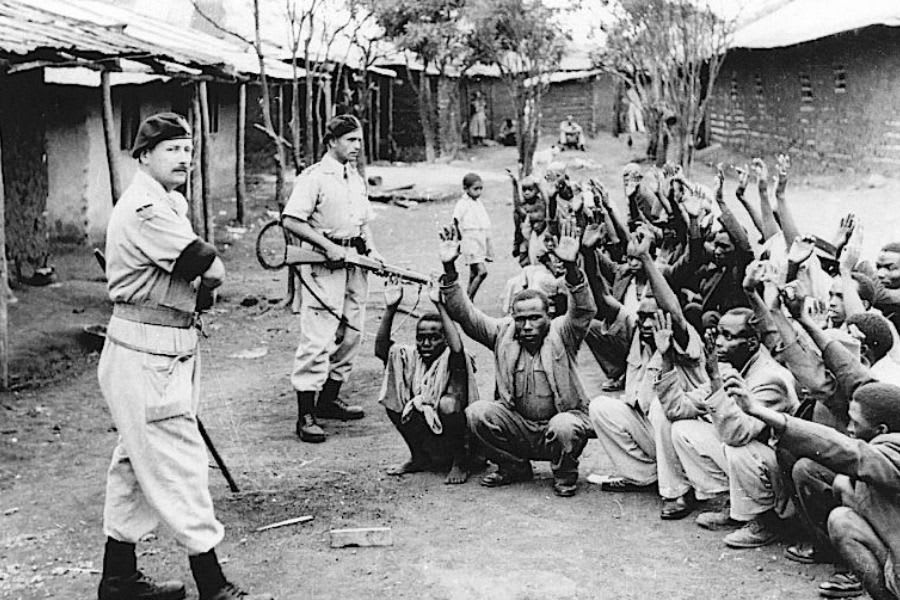

When Africa was partitioned among European powers at the Berlin Conference of 1884-85 – with Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain arbitrarily dividing African territories for European economic advancement – African minerals and oil resources were up for grabs.

As the reality of colonialism was fortifiedfrom the early 20th century till African countries attained political independence, Western multinational corporations enjoyed monopolies over Africa’s resources while Africans bore the brunt of such unbridled primitive accumulation.

With reference to oil resources, giant international oil corporations exercised unfettered dominance regarding the exploration, extraction, and global trade of oil (exportation). For instance, the Niger Delta oil region in Nigeria is ruled by Royal Dutch-Shell ever since oil was first discovered in the West-African nation by Shell-BP in the 1950s.

France also discovered oil in the 1950s and through the state oil company Elf, as well as perfectly crafted neocolonial structures post-1960, the European nation maintains the inheritances of the Berlin Conference.

Today, Western multinational oil companies are the overlords of African oil and gas resources. Foreign oil corporations in Africa rule themselves – and remit all profits back to their host countries after leaving a devastating trail of environmental damage and poverty.

Some of the Western companies maintaining their stranglehold over African oil resources mostly from America, Britain, France, Germany, among others include TotalEnergies, Royal Dutch Shell, ExxonMobil, BP, Chevron Corp., and Conoco Philips.

These foreign oil companies “run their exploration teams, offshore drilling platforms, pumping stations, pipeline-refinery complexes, helicopter pads, and tanker-fleets just as they please. Their global oil distribution networks, their investments, loans and commissions give them semi-sovereign power,” according to academic Douglas Yates.

Chinese Neocolonialism in Oil and Gas Relations with African Countries

New entrants in Africa’s hydrocarbon industry include Chinese national oil companies. Since the 1990s [primarily with Sudan in 1996), Chinese state oil corporations have gained sizeable footprints over African oil and gas resources – an industry largely dominated by Western oil multinational corporations through their sophisticated infrastructure and technology largely enabled by colonial benefits “through a series of heavy concessions”.

Some of these Chinese state oil companies include China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation (Sinopec), China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), and China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC/PetroChina).

As China’s energy demands ceaselessly surge, the country now imports oil from Sudan, Angola, Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea, and the Republic of Congo; and its ever-rising influence in this regard is felt in Gabon, Cameroon, Algeria, Liberia, Libya, Niger, Egypt, Chad, South Sudan, Kenya, Mauritius, South Africa, and Uganda.

This is against the backdrop of China being the United State’s global competitor in economic and political terms – China is Africa’s largest trading partner (having surpassed the U.S). Africa accounts for nearly 22 % of China’s oil imports, and the bulk of this trade is largely shared by Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea, the Republic of Congo, Angola, and Sudan.

Support and Criticism of Sino-African Relations in Africa’s Hydrocarbon Industry

Proponents of Chinese overtures with African petro-states view China “as a natural partner that will catalyze Afro-centric development in the context of South–South solidarity and help put an end to Western domination of the continent”. Those who voice criticism argue that “China’s intention is to exploit and dominate Africa”.

The critics of Sino-African relations pertaining to oil point to the fact that China uses the pretexts of aid-for-oil deals that lack transparency as well as the policy of “non-interference” as “it provides resources for despotic leaders who violate human rights and thereby contribute to crises, conflict, and insecurity on the continent” and that it perpetuates “the paradox of plenty, contributing to support for dictators, corruption, and dependency on Chinese NOCs, technology, and labor, making African oil producers clients of Chinese oil-fueled “neocolonialism.”

Those in support of Sino-African relations in this regard advance the notion that “China offers African petro-states the full advantage of having a ‘win-win,’ South-South, solidarity-based alternative to Western conditionalities and double standards that give Africa the opportunity to occupy the driving seat in its economic relations with external partners and use its resources for economic growth and prosperity”.

The West or China – Who is the “Better Devil” in Africa?

China has considerably improved Africa’s economic diversity through investments and loans (though it valiantly counters narratives of “debt-trap” diplomacy). The Asian giant has built factories, telecommunications structures, railroads, highways, bridges, airports, health infrastructure, and energy infrastructure.

Thus, African leaders and the citizenry perceive China as a better alternative to Western multinational oil behemoths – despite the fact that Chinese state oil companies penetrated the hydrocarbon industry through collaboration (shunning competition) with already-established Western international oil companies largely via mergers.

But while China gains immense approval in Africa via these aid-for-oil strategies and exercising soft power (for example through the learning of Chinese cultures and languages on the continent), it is infamous for human rights infringements. And some of these are exemplified through abysmal labour standards and conditions, where workers live in cramped and squalid conditions, worsened by measly wages.

The Concrete Reality of Imperial Neocolonialism – Africans Have Nothing To Gain

Before any comparison on who “the better devil” is in this much-vaunted “new scramble for Africa” – pitting Western international oil corporations against Chinese state oil corporations – the agency of African people must be considered. And that means Africa’s ruling elite/bourgeoisie.

Both the East and the West approach trade relations with Africa with one solid mentality – profit maximization. Contexts, historical trajectories, and present realities in different African countries only compel Chinese and Western oil companies to tailor their approaches to suit such material realities. African populations are seldom in charge of their own land and natural resources for their holistic economic, political, and social emancipation.

Foreign oil firms – wherever they come from – inflict serious environmental damage that poses dreadful existential threats to local populations. With the aid of Africa’s ruling elites, foreign oil companies get away with such injustice.

And worse still, they evade paying taxes, which prejudices African states as they renege their primary role of being the guarantors of life: the public provision of social services such as education, health, water, land, and food security lies in a miserable state. Aggravated of course by the neocolonial and globalized ideologies of neoliberal capitalism preaching tight fiscal austerity, privatization, deregulation, and free trade/liberalization.

African governments retain control over natural resources but benefits flowing from such are channeled towards Western and Eastern foreign firms – leaving citizens with nothing but endless cycles of poverty.

The hydrocarbon industry has ironically created miserable material realities for the people who must primarily enjoy any profits from such a lucrative but hazardous economic activity. In addition, the oil and gas sector has driven African petro-states into the abyss of dependency on one resource.

Oil is a finite resource and contributes significantly to climate change – and dependency on such a resource only acts as an embodiment of an industry that “perpetuates systems of exploitation, appropriation, and neocolonialism” in African countries.

Neocolonialism vis-à-vis African Agency

And to understand why Western imperialism ditched forceful colonialism for the more subtle and insidious neocolonial forms of domination, together with the emergence of Chinese neocolonial control – which are responsible for the continued exploitation of Africa’s oil to meet the world’s insatiable demand – the agency of African political leadership should be referenced.

When Arab nationalists in the Middle East expressed their revolutionary intentions to safeguard their oil resources for national interests – notwithstanding the successes or failures of such struggles – Western international oil corporations, later followed by the Chinese, turned their attention to Africa. Most countries in Africa were weak, focusing on nation-building and attempting to wean themselves off the influence of their former colonial masters.

Such weak post-colonial states in Africa provided a fertile ground for foreign oil firms to maximise this low risk. And this is because “oil investments are long term investments based on strategic risk assessments of possible nationalization by foreign governments.”

The collaboration of Africa’s political leadership, seized with maintaining their elite interests and proximity to state capital for self-enrichment, came, and still comes, in the form of both “authoritarian” and “democratic” leaders. Nigeria can be considered a democracy, but its oil resources are dominated by foreign firms. Equatorial Guinea has been a dictatorship since it got independence from Spain, and its oil resources are dominated by foreign firms.

While the machinations of contemporary neocolonialism cannot be cast away, the agency of Africa’s leadership cannot be put aside either. Multinational oil companies will hardly change their ways. Africa’s leadership – whether democratic or autocratic – will not change either.

Conclusion – Change Starts From Within: Reduce Consumption of Oil

What matters is ascertaining the root cause of this unending imperial and neocolonial exploitation of Africa’s natural resources, in this context, oil. As long as the global demand for oil does not subside, it is futile arguing for a change of behaviour from Western multinational oil firms and Chinese state oil firms. Or arguing for pro-democracy politicians to get into power either through elections or foreign interventions.

As put by Douglas Yates, “Reducing oil consumption reduces the funding for corrupt systems of collaboration in the African oil business. It requires no military intervention, nor any unrealistic oversight of world oil markets. [Ethically], it is better to seek to change oneself than it is to try to change others. For, in the final analysis, we are the reason for the scramble for African oil.”

This, coupled with the holistic nationalization of oil and gas resources by African peoples, will lead to the holistic, emancipatory, inclusive, and genuinely democratic transformation of African livelihoods.