The concept of ‘human rights’ in its contemporary, universal and globalized understanding is arguably a new one. Yet, this is not to say that the rights of human beings have been historically non-existent, only to surface as a 20thcentury post-war invention. Human rights are probably as old as human existence.

Every ancient civilization that ever existed knew that the human being is inherently entitled to a dignified life - filled with the inalienable sacrality of human life. Human rights are grounded in humanity.

The only difference is that whereas the human rights concept is now universally institutionalized through written international and domestic laws, ancient civilizations applied them selectively because of the prevailing economic modes of production and the attendant relations of production they were familiar with. And this carried significant points of deviation geographically.

For instance, in ancient Western civilizations, slaves and peasants had minimal rights compared to the patriarchal upper classes - the era of slavery and feudalism. In ancient African civilizations, rights were centered on the indispensable aspect of communal life to ensure some sort of egalitarian relations of production, but patriarchal leaders had more privileges than the rest of society.

Human rights are humanity itself - human rights are human existence. And today, it is now widely established and accepted that human rights are applicable to everyone regardless of obstructive factors such as race, class, gender, religion, ethnicity, sex, etc.

The contemporary discourse on human rights in Africa tends to be specious because of certain failures and transgressions - through omission and commission - of the continent’s postcolonial states, as magnified by neocolonial stereotypes advanced largely in Western media (as well as social media).

Thus, it is not surprising for human rights narratives in Africa to assume contorted meanings in which Africa as a whole is essentially “othered”. Perhaps many are losing faith in the sanctity of human rights as they are realized in Africa because of globalized capitalism’s contradictions.

Questions on whether “human rights are the necessary tools for Africa’s transformation” or “human rights in Africa are neocolonialism’s imposition” or “human rights are the last refuge of the privileged/elite” abound globally and on the continent.

Since the modern understanding of what human rights are was shaped via Eurocentric views after World War II, it is justifiable to ask such questions - for this understanding tends to be riddled with double standards because of how it disregards the existence of “human rights norms in other cultures.”

Yet, human rights in Africa should not take such a turn, because Africans are human beings like the rest of the world’s populations and equally deserve the realization and materialization of these rights - which are inalienable. It is negligent not to mention the existence of human rights frameworks intrinsically commonplace in African societies; in the precolonial era as well as in the colonial era when struggles for liberation were waged.

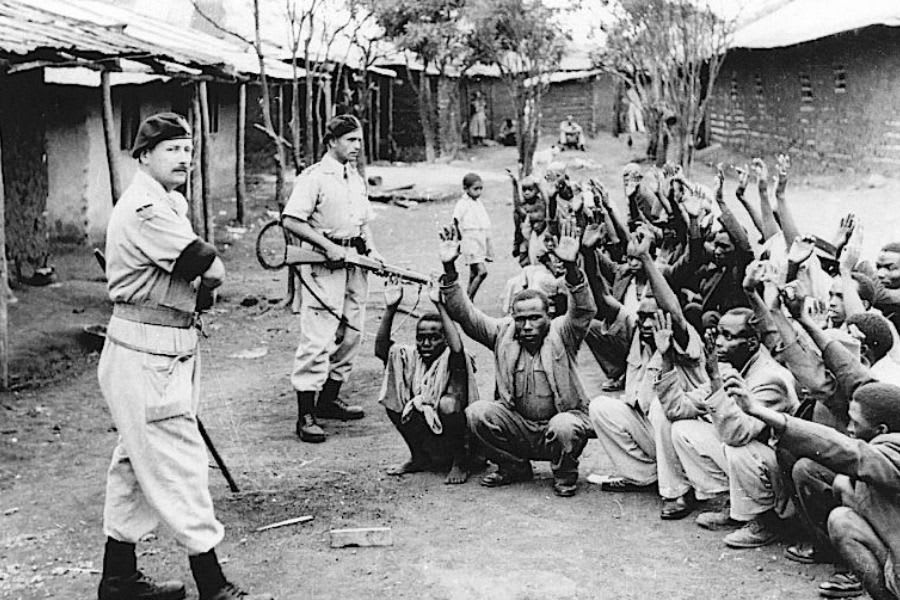

Before Western liberal traditions of democracydestroyed indigenous African knowledge systems - economically, politically, and socially - robust frameworks that realized the nature of human life were celebrated and upheld with respect in African societies.

The African idea of holistic human rights for well-functioning communities was hinged on the perception of man and woman as “social beings” - the “bearers of rights and duties”. This meant that everyone knew their role to play in the public wellness of the community - everyone had an immutable conception of the rights they are entitled to.

For these rights to be respected, one had to perform their duties; thus curbing individualism by striking a balance between rights and duties - the complete realization of “human dignity”.

Such a “rights-duties'' approach on societal justice in pre-colonial Africa was also predicated on ensuring the cohesion of the collective as a whole. The realization of “justice” and “human dignity” in pre-colonial Africa was not wholly premised on the sanctification of individual rights in their independent state - as in the possibility to lay “individual claims against the state”.

This is not to say African societies then were nonchalant about the rights of the individual. If anything, the wellness of the public was supposed to be reflected in the individual’s wellness. Likewise, the public well-being could only be achieved by building a society with individuals who led dignified lives.

Although some critics would favour drawing a line as regards this rights approach - that the term “human rights” cannot be applied to pre-colonial Africa; since European liberalism emanating from Enlightenment emphasized the individual’s civil liberties in a money economy - it is essentially the same thing.

That the African notion of justice is “rooted not in individual claims against the state, but in the physical and psychic security of group membership” affirms the idea that such a notion realizes individual rights as well.

The security of group membership comes to life where each individual’s existence is respected through the dichotomy of “rights and duties.”

However, even if pre-colonial notions of rights discourses differ in applicability to contemporary universal human rights, this does not mean that Western liberalism does not command validity in human rights narratives. Regardless of these different understandings, the modern concept of universal human rights is not entirely a Western affair.

As such, human rights in Africa are not an imposition of (neo)colonialism - it is clear that much of today’s human rights were central in pre-colonial Africa, although they were not written down or spelled out. It goes without saying that since time immemorial the arbitrary taking of another individual’s life - murder - has always been outlawed in virtually all human societies.

What is salient to note is that in the case of royal families (mostly based on patriarchal lines of inherited leadership) were above the law only for the purposes of maintaining social order, cohesion, and for providing moral, spiritual, political, and economic guidance. They presided over the judicial systems for dispute resolution. Even with such privilege, leaders had to discharge their duties.

The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights ushered in the contemporary concept of universal human rights. By institutionalizing human rights, the aim is “to achieve the freedom/protection of the common man and the less privileged from the oppressive show of power and force of the privileged ones”.

The postcolonial states in Africa should re-imagine their human rights frameworks so as to “inform it with an African perspective, that of the twinning of duties and rights in a society consumed by the socialization of the individual, a concept articulated by the 1981 African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights” according to scholar Makau wa Mutua.