At first glance, the Upemba Depression in south-east Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is merely a geographical wonder; a 200 kilometre-long marshy bowl area comprising about fifty lakes. However, beneath the surface are various windows into ancient African history. Between the 1950s and 1980s, Belgian archaeologists chose 6 out of the identified 40 archaeological sites to excavate, uncovering over 300 graves.

These graves revealed an abundance of information about the peoples who inhabited the area centuries ago, including previously undiscovered details about the ancient Luba Kingdom. The items found in the graves (grave-goods) suggested that these societies made economic, technological, social and political developments outside of extra-continental influence. Today, the grave-goods are part of archaeological collections showcased in the Musée National de Lubumbashi in DRC, the Royal Museum for Central Africa and the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Belgium, DRC’s former coloniser.

The excavated sites of the Upemba Depression were Katongo, Sanga, Kikulu, Kamilamba, Malemba-Nkulu and Kisale. Based on these, scientists were able to identify 4 main societal time periods which we will be exploring in this article.

The Kamilambian (mid-6th to 8th century)

The Kamilamba site, at the northern end of the depression, has been used by archaeologists to name the earliest period of farming settlement in the Upemba Depression. Radiocarbon dating showed that the grave-goods point back to a period that started 1,500 years ago, around the mid-sixth century.

Archaeologists found a few pots, iron artefacts, grinding stones and palm nuts, but no copper. The pottery was decorated with comb impressions and bore resemblance to the ironworking group pottery traditions in northern Zambia and the Copperbelt just 400 kilometres south of the depression. Pieces of hardened mud with reed impressions were also found, suggesting houses of that period were built with these materials.

The absence of imported materials shows that the Kamilambian people were likely not a part of the regional trade networks that started to develop around the Copperbelt at that time. However, other items suggested they related with other peoples to the west in DRC and Angola and to the east, northern Zambia.

Early Kisalian (mid-8thto late 9th century)

The Early Kisalian period, named after Lake Kisale also in the northern half of the depression, is dated to a little over 1,000 years ago. It seemingly developed from the Kamilambian period due to the persistent use of comb impressions in pottery, amongst other similarities.

However, changes in material culture and funerary practices showed that the society had evolved in some ways. In the relatively few graves explored, archaeologists discovered iron hoes, knives and spearheads, pottery and rare copper objects, which were mainly bracelets and anklets. In two of the wealthiest graves, there were ceremonial iron axes and nail-studded wooden handles, suggesting that there were local leaders. In one of the graves, and a few pots, there was also a cylindrical iron anvil which had traditional symbols of authority typical of Bantu peoples like the ones on the axes.

The area’s population seemed to be relatively small, but the copper items suggests that Upemba Depression was likely becoming part of a trade network to which they probably primarily contributed fish. Copper’s colour and attributes like ductility and malleability, allowing for ease of workability, made it highly valued across the continent over centuries.

Classic Kisalian and Katotian (late 9th century to 13th century)

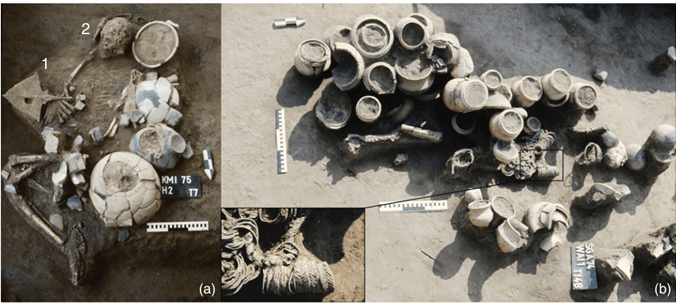

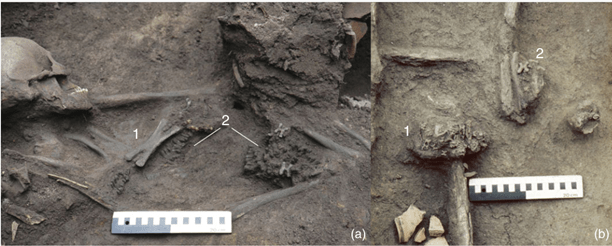

The Classic Kisalian period succeeded the Early Kisalian about 1,000 years ago and lasted several centuries. The size and number of sites (5) and graves suggest that there was significant population growth during the period. Grave-goods included informative skeletal remains, as well as farm tools, fishing tools, weapons and accessories (like bracelets and belts) made of either iron or copper. There were also peculiar items like bracelets and necklaces made of finely carved ivory, leopard teeth and high quality pots with distinct designs.

More interestingly, the quantity, quality and nature of the grave-goods appeared to vary with the sex, wealth and status of the deceased. There was evidence of complex burial practices among the Classic Kisalian society as the depth of graves seemed to depend on age; adults were buried deeper than children. Additionally, burials were typically in an extended or slightly flexed position, on the back or on the side. Some of the intricate pottery was clearly made for burial purposes as they were too small for practical use and the ones in children’s graves appeared to be proportional in size to the age of the deceased. Moreso, multiple burials situated in the same place suggest that human sacrifices may have been made after the death of a notable person.

During the same period, archaeologists also found that there was another people group that existed, but their graves were found in Katoto, a site in the southern half of the depression. The so-named Katotian society were peculiar in that they seemed to bury whole families together; many graves occupied by a single man with woman and children were found. They also seemed to have more relations with the Indian Ocean trade route as their wealthiest graves had almost 150 cowries, a dozen glass beads and eight conus shells compared to the few cowries and glass beads found in the Classic Kisalian graves. However, common to both the Classic Kisalian and Katotian peoples was burials with status symbols such as iron ceremonial axes, bells and anvils from the East African coast.

Archaeologists believe that the era of the Classic Kisalian and Katotian societies was the peak of cultural development in the region. This is because of the copious evidence of agricultural activity in the form of iron hoes, grinding stones and livestock bones, which were part of the grave-goods. Additionally, there were harpoons, fish hooks and fish bones found amongst the grave-goods, suggesting that their major agricultural practice was fishing. Some of the pots appeared to serve as braziers as their rims had vertical extensions for supporting other pots—this would have helped them to cook fish in canoes, a practice that exists till today. It is believed that the high protein intake from fishes supported the increased population density in the region and in turn, its impressive cultural development.

The most remarkable aspect of these societies were their technological advancements, having produced sophisticated weaponry, tools and ornamental items by hammering and wire-drawing techniques. Their ivory carving skills and pottery making were also exceptional. Additionally, scientists believe that there were a range of skills, such as basketry, that involved using organic materials which would not have survived a millennium.

Most importantly, the excavated evidence points to some social and political attributes of the ancient societies of the Upemba Depression. For instance, the Classic Kisalian society was evidently a hierarchical one in which chiefs probably wielded political and ritual power while their underlings had varied wealth and social status. Women had some of the wealthiest graves, suggesting that women held notable roles during the period. Moreso, it could be surmised from the continuity of the burial traditions that there was political stability and good order during the period. Yet, this was likely an early stage in state development marked by social boundaries and fragmented power rather than geographical borders and centralised authority. Also, the society’s way of life was seemingly free of the external influences that are widely said to be responsible for similar developments in other parts of Africa.

The extensive use of copper in the Classic Kisalian period suggests that by then, a considerable trade had developed with the Copperbelt and other communities. However, the few trade goods that reached the region from the East African coast, about 1,500 km away, suggests that the trade contacts were likely minor and indirect.

Kabambian (13thto mid-18th century)

This period, named after Lake Kabamba at the northern end of the depression, dates back to about 700 years ago. It was marked by a change of burial rituals as grave-goods, especially those considered to be symbols of authority, became fewer and pottery less elaborate. Simultaneously, there were distinctive copper cross-shaped ingots that served as a form of currency.

Scientists have divided this period into Kabambian A (13th to mid-15thcentury) and Kabambian B (mid-15th century to mid-19thcentury) as further changes in burial practices and pottery were discovered about 500 years ago. The Kabambian B sub-period was characterised by even fewer grave goods and smaller and more uniform copper crosses, suggesting that they now became a general-purpose currency rather than a special-purpose currency as in the preceding sub-period. The use of a general-purpose currency implies that there was a more centralised political authority during the Kabambian B sub-period. This checks out because according to oral traditions, the Luba Kingdom emerged about 200 years ago, which would likely be the end of the Kabambian B sub-period.

The Luba Kingdom oversaw a large area of savanna south-east of the Central African forest. By this time, the Upemba Depression had developed wide inter-regional trade relations and the presence of cowries and glass beads in Kabambian B graves indicates a rising contact with the Indian Ocean coast. The Luba Kingdom seemed to have originated in the Upemba Depression, although its capitals were located outside of the region.

All in all, the astounding discoveries made in the Upemba Depression were enough to earn it considerationfor the title of UNESCO World Heritage Site. By practicing a custom as simple as burying items with their corpses, the ancient societies of this region have communicated to subsequent generations what nature could never unveil on its own. One can only wonder if these peoples realised how crucial their burial customs would be to the preservation of our history.

Oyindamola Depo Oyedokun

Oyindamola Depo Oyedokun is an avid reader and lover of knowledge, of most kinds. When she's not reading random stuff on the internet, you'll find her putting pen to paper, or finger to keyboard.

follow me :

Leave a Comment

Sign in or become a Africa Rebirth. Unearthing Africa’s Past. Empowering Its Future member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.