Kongo, located in modern-day Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), was one of the great kingdoms of pre-colonial Africa. Emerging in the 14th century, the Bantu kingdom experienced centuries of immense affluence and power until conflicts with Portugal and internal division decimated it, leading to its total collapse in the 20th century.

In this article, we will discuss how the powerful kingdom came to be, the events that led to its downfall, and its cultural and historical relevance today.

The Great Kongo Kingdom

According to traditional accounts, Lukeni lua Nimi founded the Kongo Kingdom circa 1390. However, some sources claim its founding in the 15th century and its discovery by Portuguese explorer Diego Cao, who landed at the mouth of the Congo River in 1484.

The Bakongo (people of Kongo) originally occupied a narrow region south of the Congo River from modern-day Kinshasa to the port city of Matadi in the lower Congo. However, after several conquests and treaties, the kingdom assimilated neighboring tribes, including the Bambata, Mayumbe, Basolongo, Kakongo, Basundi, and Babuende.

In its prime, during the 16th century, Kongo’s territory spanned over 600 km, extending as far as the Kwango River to the east, the Dande River to the south, and Kwilu River to the north. At this time, it had a population of well over 2 million people.

Kongo’s economy was initially sustained by the regional trade in copper, ivory, salt, cattle hides, and slaves along the Congo river. Additionally, craftworkers such as weavers who made the famous raffia fabrics of Kongo, potters, and metalworkers contributed to the kingdom’s impressive local production sector.

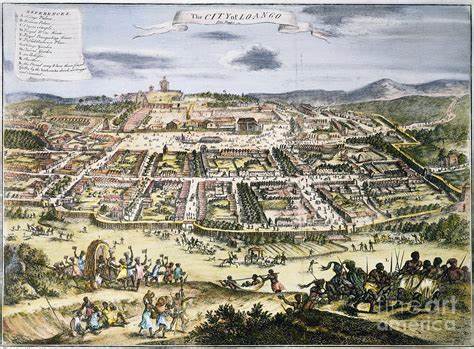

Kongo was ruled by a single monarch, the manikongo (king of Kongo), who appointed governors to oversee the various regions throughout the territory. The governors collected tributes in the form of millet, ivory, palm wine, and wild animal skins, presenting them to the manikongo at extravagant annual ceremonies in Mbanza-Kongo, the kingdom’s capital. In return, the governors obtained military protection, luxurious gifts, and “divine favor,” as the manikongos were believed to be direct links to the spirit realm.

The manikongos were distinguished by symbols such as a headdress, a royal stool, a drum, and regal jewelry made from ivory and copper. To enforce their authority, they controlled an army of slaves, which in the 16th century numbered as many as 20,000 men.

The Bakongo and the Portuguese

While the Kongo economy was already thriving based on just regional trade, the arrival of the Portuguese towards the end of the 15th century significantly strengthened the economy, especially regarding the slave trade. The Portuguese exchanged cotton clothing, silk, glazed china, glass beads, etc., for the Bakongo's abundance of slaves.

In 1491, the ruling manikongo Nzinga a Nkuwu and his son, Mvemba a Nzinga, were baptized by Portuguese missionaries and adopted the Christian names João I and Afonso I, respectively. This made João I the first Christian king of Kongo. However, it was Afonso I who institutionalized Christianity in the kingdom after ascending the throne in 1507, earning him the moniker “The Apostle of Kongo.” Under his leadership, the Bakongo became the first sub-Saharan African people to adopt Christianity, albeit their version of Roman Catholicism.

Additionally, Afonso I established strong diplomatic ties between the kingdom and Portugal by reaching an agreement called the Regimento with Manuel I of Portugal in 1512. The Regimento entailed the kingdom’s acceptance of Portuguese institutions, provision of extraterritorial rights to Portuguese subjects, and supply of slaves to Portuguese traders. Afonso I also extended Kongo’s territory and centralized its administration.

In 1526, the peaceful relationship between Afonso’s Kongo and the Portuguese was disturbed when he discovered that Portuguese merchants were purchasing illegally enslaved persons and exporting them—legal slaves were usually prisoners of war or people who were unable to pay their debts. This realization led Afonso to set up an administrative system to supervise the slave trade. He also strove, albeit unsuccessfully, to restrict Portuguese relations to his kingdom alone.

Towards the end of Afonso’s reign in 1542, there was great contention over his succession, leading to several political plays and even an assassination attempt on his life by the Portuguese. Years after Afonso’s reign, disputes concerning the manikongo succession ensued and spurred the division of the kingdom into rival factions.

Consequently, in 1568, the kingdom was overcome by rival warriors from the east known as the Jagas. The manikongo at the time, Alvaro I Nimi a Lukeni, was only able to restore the kingdom with Portuguese assistance. In exchange, he allowed the Portuguese to settle in Luanda (then part of Kongo territory) and later create the colony of Angola.

However, relations between Angola and Kongo soon soured when the former’s governor briefly invaded the latter in 1622. Then, from 1641 to 1648, the ruling manikongo, Garcia II Nkanga a Lukeni, allied with the Dutch to seize portions of Angola from the Portuguese. Further conflicts between Portugal and Kongo regarding joint claims in the region culminated in the Battle of Mbwila on October 29, 1665, which ended in Portuguese victory and the decapitation of the ruling manikongo Antonio I Nvita a Nkanga.

Division in the Kongo Kingdom

Following the Battle of Mbwila, the unified kingdom of Kongo was essentially no more. Two rival factions, the Kimpanzu and Kinzala, contested the kingship and started a civil war that dragged into the 18th century. The war resulted in the destruction of the countryside and the sale of several thousand Bakongo into the Trans-Atlantic slave trade.

The rival factions established multiple semi-independent bases throughout the region and decided to rotate the kingship among themselves, an agreement initiated by Pedro IV Agua Rosada Nsambu a Mvemba. During that time, Mbanza-Kongo was seized by the Antonians, a religious sect hoping to create a new Christian Kongo Kingdom. In 1709, Pedro tried and executed the sect’s leader, Beatriz Kimpa Vita, as a heretic, reclaimed the capital, and restored the kingdom.

The rotational kingship system persisted well into the 18th century, allowing for the long reigns of Manuel II Nimi a Vuzi of the Kimpanzu (1718-43) and Garcia IV Nkanga a Mvandu of the Kinlaza (1743-52). However, the system was not hitch-free, as smaller-scale factional disputes about succession occasionally ensued, resulting in a weak monarchy.

At some point, Portugal had to step in to settle the succession dispute that followed the death of Henrique II Mpanzu a Nzindi (1842-57), thereby allowing for the installation of Pedro V Agua Rosada Lelo in 1859. Pedro V later relinquished his territory to form part of Portugal’s Angola in exchange for increased royal powers over outlying areas.

The final straw triggering the collapse of the Kongo Kingdom was a revolt led by Alvaro Buta against Portuguese rule in 1913-14. The revolt was suppressed, and the kingdom was then fully absorbed into Angola.

The Aftermath

Following the kingdom’s integration into Angola, there were strong attempts to resurrect Kongo nationalism and culture.

In 1921, Simon Kimbangu, a member of the English Baptist Mission Church, started the Kimbanguism movement, which became a launchpad for anticolonial sentiments in the Belgian Congo (now DRC). Kimbangu, claiming a divine mandate, spoke against the church and colonial government. His activism earned him an arrest and a life in prison sentence, commuted from a death sentence. After his death in 1951, his legacy lived on as Kimbanguism gained legal recognition from the state. The Kimbanguist Church championed the Mobutu regime and today has over 300,000 active members.

European historians and missionaries, such as Georges Balandier and Father Van Wing, helped unearth the glorious past of the Kongo Kingdom. Some argue their actions inspired Bakongo intellectuals in the Belgian Congo to demand independence from Belgium in 1956. These intellectuals formed a political party whose candidates won the majority of municipal seats in 1959, leading to the election of President Joseph Kasavubu in 1960. Kasavubu, a Mukongo (person of Kongo), was the first president of the independent DRC (then the Republic of Congo).

Today, the Bakongo constitute the largest ethnic group in the Republic of Congo and the third largest in Angola. Mbanza-Kongo remains significant as the capital of Angola’s northwestern Zaire province and was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2017.

Oyindamola Depo Oyedokun

Oyindamola Depo Oyedokun is an avid reader and lover of knowledge, of most kinds. When she's not reading random stuff on the internet, you'll find her putting pen to paper, or finger to keyboard.

follow me :

Leave a Comment

Sign in or become a Africa Rebirth member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.

Related News

The Real Reason Why Africa Was Called the Dark Continent

Oct 31, 2023

The Rise and Fall of the Ancient Asante Empire

Oct 29, 2023

10 African Countries that Changed Their Names and Why

Oct 24, 2023