The institution of chieftaincy is one of the most enduring traditional institutions in Africa. In spite of many alterations, it continues to display remarkable resilience from colonial to post-colonial times. A number of studies have affirmed the resiliency, legitimacy and relevance of African traditional institutions in the socio-cultural, economic and political lives of Africans, particularly in rural areas.

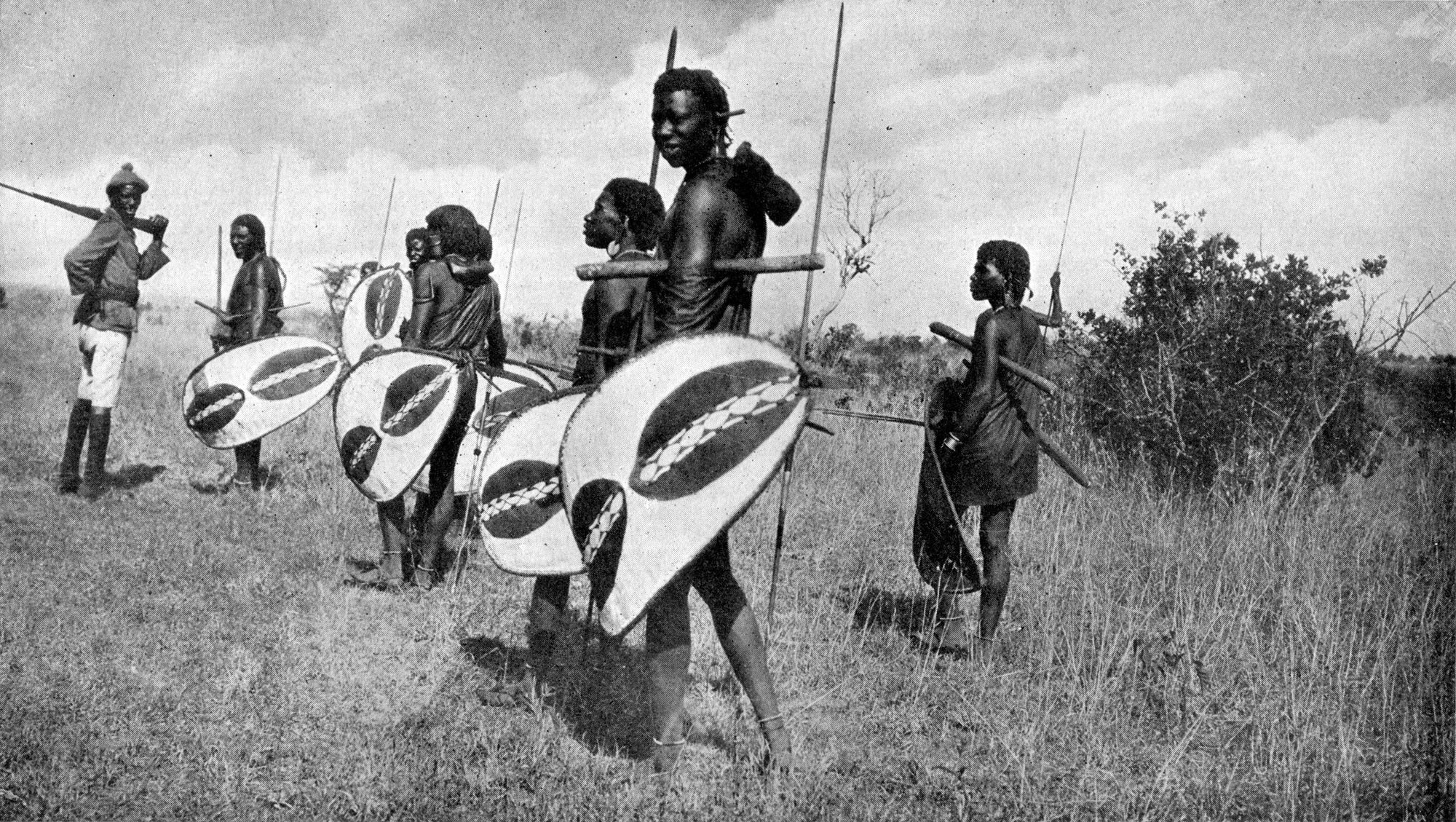

Historically, chiefs constituted the confederation for the exercise of executive, legislative, judicial, military, economic and religious roles. African countries are usually characterized by fragmentation of various aspects of their political economy, including their institutions of governance. Large segments of the rural populations, which are a majority in most African countries, continue to adhere principally to such traditional institutions.

The roles that the chieftainship plays in the process of good governance can broadly be separated into three categories. The first is their advisory role to the government, which goes hand in hand with their participatory role in the administration of regions and districts. The second is their developmental role, which complements the governments’ implementation of development projects such as sensitization on health issues like HIV/AIDS, promotion of education, encouragement of economic enterprises, as well as the governments’ efforts to inspire respect for the law and urge participation in the electoral process. The third role is conflict resolution, an area where traditional leaders across Africa continue to demonstrate great success.

There are differences in the degree to which chiefs can define tradition; more powerful chiefs, who work as allies with the government, have a greater say in which traditions should be considered useful or redundant. Stand-alone chiefs who operate in rural ares, on the other hand, do not have such authority, so they try to assert their chieftainship by emphasizing their foundation in tradition, and using their professional and international experience to spur local development and modernize the chieftaincy institution. Chiefs often demonstrate their status in the public eye by performing, dressing and adhering to the protocols of royal conduct and rituals.

According to Moagi Molotli, a council man in the village of Serowe in Botswana, “Chieftainship was the cornerstone of Botswana’s (and most African countries’) political life, both before and during the colonial era. Before the establishment of the British Protectorate of Bechuanaland in 1885, for instance, the Setswana tribes, like other Sotho people, had for centuries enjoyed an elaborate political system – which depended on the chief being vested with absolute powers. However, before 1885, external pressures did not ultimately prevent internal revolt, which is the reason why eventually, administrators (often foreign) were also appointed to supervise chiefs.”

Most African countries are characterized by parallel institutions, one representing the formal laws of the state and the other representing the traditional institutions that are adhered to more commonly in rural areas. The two systems do not clash, but instead integrate effectively in order to better serve citizens in terms of representation and participation, service delivery, social and health standards as well as access to justice. Although, they do sometimes contradict each other, which creates problems such as institutional incoherence.

According to Amma Muchenya, a historian from Ghana, “Before colonial rule, Ghana as we know it comprised of many independent states and kingdoms. These were large powerful kingdoms with a number of vassal and satellite states. Each kingdom was headed by a supreme ruler, who acquired his position through hereditary succession. These supreme rulers would then operate under the centralized political systems. However, post-independence, things changed; now, members of parliament and the district chief executive, who facilitate the provision of infrastructure and basic amenities in districts and constituencies, are held in higher esteem than chiefs. The chieftaincy now plays the role of advisory on traditional matters.”

Traditional institutions have continued to metamorphose under the postcolonial state, as Africa’s socio-economic systems continue to evolve. Despite this, these institutions are referred to as traditional, because they are largely borne out of the precolonial political systems and are adhered to principally by the populations in the traditional (subsistent) sectors of the economy.