Today, South Africa is one of the most ethnically diverse countries in the world. However, centuries ago, before European penetration, the region that is now called South Africa only housed various indigenous African tribes.

The southernmost African country has a long, complicated history with Europeans and colonialism. However, the first major interaction between people of present-day South Africa and Europeans can be traced back to the late 16th century. In exchange for local cattle, European ship crews traded iron, copper and other goods with the Khoikhoi and San peoples—collectively known as the Khoisan—in the Cape of Good Hope. For the Khoisan, the trade relationship was double-edged, ushering in economic prosperity, but also giving room for Dutch infiltration.

The Dutch Settlement in the Cape

In the 17thcentury, a Dutch company called Dutch East India Company, or Veereengide Oostindische Compagnie (VOC), was the largest trading enterprise in the world. In order to conduct trade in the region they called East India (in present-day India and Indonesia), VOC would need to send its workers on long voyages by sea. However, the sailors often suffered from malnutrition and resultant illnesses. This necessitated the development of a place where they could get refreshed mid-journey. Thus in 1652, VOC dispatched Jan van Riebeeck and an expedition of 125 men to set up a fort (Fort de Goede Hoop) and provision station for Dutch ships in the Cape of Good Hope.

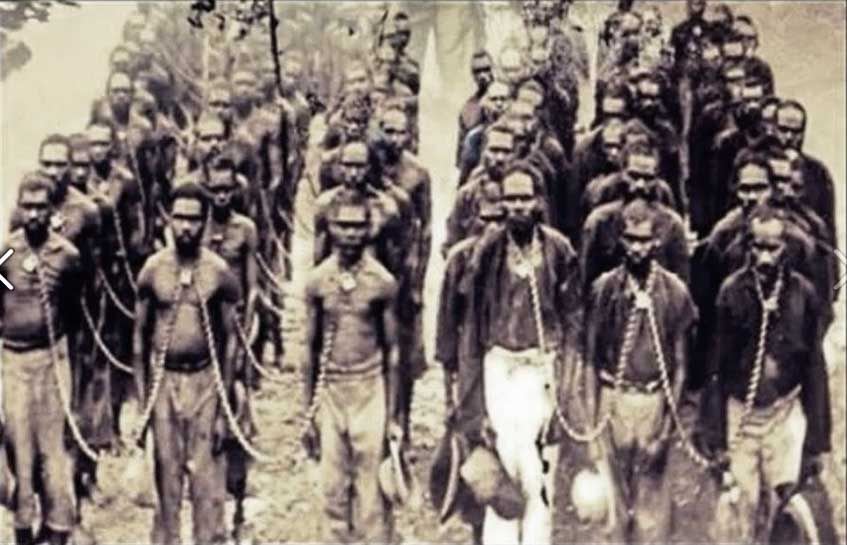

Not too long after Riebeeck set up the Fort, the outpost grew into a proper settlement of Dutch people as Riebeeck saw the economic potential in the region. By 1657, VOC had released some of its servants as free burghers (citizens), allowing them to cultivate land and herd cattle on the company’s behalf. The next year, slaves arrived from a Dutch ship, which had seized them from a Portuguese vessel en route Portugal from Angola. Afterwards, slaves continued to arrive from Madagascar and parts of western and eastern Africa.

VOC forbade the enslavement of the Khoisan, however, the Dutch’s incessant demands for cattle and encroachment of their grazing lands and waterholes became overbearing for the Khoisan, but the Khoikhoi especially. The latter soon had limited access to their own resources and were reluctant to trade in cattle. Since the Khoikhoi were a nomadic tribe, they felt they should have access to all the land in the area for cattle grazing, but the burghers laid exclusive claim to some of the land.

The First Khoikhoi-Dutch War (1659-1660)

Fed up by the Dutch encroachment, Doman, a Khoikhoi tribesman and interpreter who lived in Fort de Goede Hoop, led some of his people in multiple cattle-lifting excursions against the Dutch settlers. The Khoikhoi hoped that these thefts would discourage the settlers from farming, thereby leaving more grazing land for themselves. Unfortunately, their plot did not bring about the desired result.

In 1659, the settlement farmers protested against the recurrent cattle theft and called an urgent council meeting with Riebeeck. The council, comprising representatives of VOC and free burghers, convened to discuss the issue at hand. Although both the company and the burgers were not inclined to war, they saw no other way to achieve eventual peace in the area than to declare war on Doman’s clan.

Interestingly, while the council meeting was ongoing, Doman and his people attacked a farm and killed the cattle herder, a boy named Simon Janssen. News of the attack soon reached the Fort and consequently, panic ensued among the Khoisan clans, with the Strandloper (Khoikhoi) clan even fleeing to avoid being caught in the crossfire.

Burghers who could not defend themselves were evacuated to the Fort, while guards were deployed to protect the families who stayed on the farms. More soldiers arrived by ship and guard houses were established along the border of the settlement. Doman’s clan were difficult to capture and often brilliantly attacked the settler troops on rainy days, when their gunpower would not ignite.

Riebeeck decided to take the following security measures for the settlement: deepening existing strongholds, building three additional watch-houses, putting up a strong fence, mounting patrols along the line and placing Boerboel dogs on farms. The fence line marked the official border of the settlement.

During the war, a severe sickness broke out among the settlers’ cattle, killing at least 80% of some of the affected flocks. The settlers set up a weekly prayer meeting to pray for relief from the trying situation.

Another Khoisan clan, led by Oedasoa, who were also at war with Doman’s clan opted to forge an alliance with the settlers. While the council was reluctant to accept any men from Oedosoa’s clan, it accepted Oesdosoa’s advice on expedition matters. The Dutch were able to bring in 105 additional European soldiers, thereby bolstering their defence at the Cape. This additional support empowered the settlers to carry out several expeditions, albeit largely unsuccessfully.

Fights broke out between the mounted patrols and Doman’s party on multiple occasions, with the latter being on the losing side most of the time as they could not compete with the settlers’ weaponry. During one of the fights, Doman was wounded and his party scattered.

On 6 April, 1660, Doman and his followers arrived at the Fort and signed a peace treaty with the settlers. Both sides agreed not to attack each other in the future and it was stated that Doman’s people would only enter designated points of the settlement territory for the purpose of trade. Furthermore, it was declared that the free burghers and VOC would retain ownership of the land they occupied and that the former would not treat the locals harshly for the events that transpired during the war.

The Aftermath and Subsequent Uprisings

The Second Khoikhoi-Dutch War (1673-1677) had less to do with the poor treatment of the locals by the settlers. Rather, it was sparked by a Khoikhoi clan’s grievance with the trade between the settlers and their enemy clan. Members of the Cochoqua clan, led by chief Gonnema, attacked and killed Dutch hunters on multiple occasions because of the settlers’ affiliation with the Chainouqua clan—the two Khoikhoi clans were at war with each other at the time. The Cochoqua attacks escalated into a full blown war as the settlers retaliated and even allied with the Chainouquas. Eventually, the Cochoquas lost out and a peace treaty was signed between the three parties.

By the late 18thcentury, European settlers in Cape—called Boers—had significantly multiplied. The settlers weren’t all Dutch, but VOC had mandated that they all speak Dutch and practice a denomination of Christianity called Calvinism. Thus, the settlers largely had a shared sense of identity and began to call themselves Afrikaners.

Once the Afrikaners were able to cross the range of mountains inland from Cape Town and overcome the Khoisan resistance, they spread rapidly across the region. They ruled over their slaves and Khoisan servants and clients with an iron fist as they feared possible revolts from them—the slaves and Khoisan were much larger in number. As the Dutch expanded, they eroded the Khoisan resources through forced trade, plunder and human and cattle disease. The Khoisan retaliated in pockets of uprisings, involving cattle theft and burning of settler homesteads.

The presence of slaves denied the Khoisan of significant economic opportunities. By the late 17thcentury, many Khoisan served the Europeans as servants—just a rank higher than slaves. In theory, the Khoisan servants were free. However, in reality, European masters forcefully led their Khoisan servants.

As the Cape grew a bigger stake in the world economy, the demand for food from European ships and increased controls over Khoisan labour heightened. In 1775, a system whereby Khoisan children were apprenticed until the age of 25 was adopted. And by the end of the century, the Khoisan were subject to a similar system to the slaves, impeding their mobility. As they lost their cattle and grazing areas, the Khoisan virtually became slaves on settler farms. Only a few managed to escape out of the colony.

Between 1799 and 1803, dispossessed Khoisan farmers—many of whom had horses and guns—in Graff-Reinet revolted against the burdensome colonial order imposed by the Dutch. The Dutch feared that the Khoisan, now joined by Xhosa allies, would attack the arable farms of the southwest. However, owing to divisions among Khoisan and Xhosa forces and the intervention of (British) government troops, the uprising was defeated. This was the last time the Khoisan fought for their lands under their traditional rulers.

By the end of the 18thcentury—at the time when the British had taken over—the small VOC outpost had become a full-blown settlement in which over 20,000 Europeans dominated a labouring class of about 25,000 slaves and Khoisan each. There was also a growing number of Xhosa in the eastern districts.

Today, the Khoisan are arguably the most sidelined ethnic groups in South Africa and are even in danger of extinction, a testament to the far reaching effects of their oppression by the first Dutch settlers.

Oyindamola Depo Oyedokun

Oyindamola Depo Oyedokun is an avid reader and lover of knowledge, of most kinds. When she's not reading random stuff on the internet, you'll find her putting pen to paper, or finger to keyboard.

follow me :

Leave a Comment

Sign in or become a Africa Rebirth. Unearthing Africa’s Past. Empowering Its Future member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.

Related News

Congo’s Unfinished Revolution: Patrice Lumumba and the Struggle for Sovereignty

Jun 01, 2025

How Ancient Mombasa Became the Gateway of African Commerce

May 31, 2025

How Mozambique Broke Free from 500 Years of Portuguese Rule

May 30, 2025