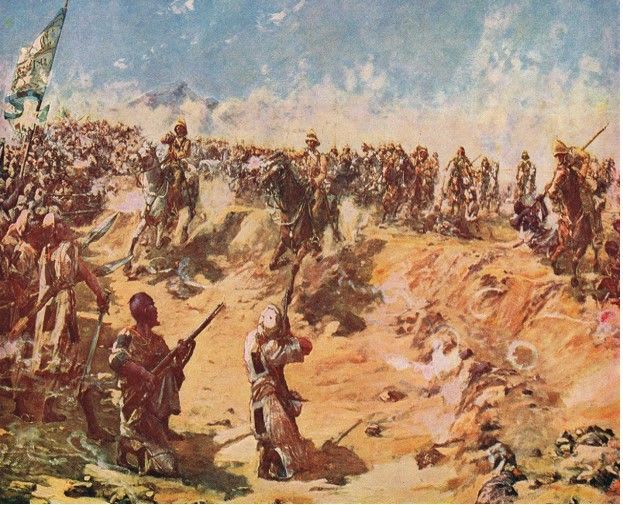

The Battle of Omdurman, which occurred on September 2, 1898, was the major point in the 18-year-long Mahdist war that determined the victory of the British over the Mahdist movement in Sudan. British General Horatio Herbert Kitchener led Anglo-Egyptian forces to defeat the Mahdist leader, Abd Allah Ibn Muhammad Ataishi – or simply “Abd Allah” – and consequently won the Sudanese territory which the Mahdists had dominated since 1881.

What Triggered the Mahdist Movement?

In 1821, Sudan was made a dependency on Egypt which was a province of the Ottoman Empire. Sudan would then be governed by the same multiracial Turkish-speaking class that ruled Egypt. In 1877, an Anglo-Egyptian Slave Trade Convention, which dictated that the sale and purchase of enslaved people in Sudan was to cease completely by 1880, was signed. Charles George Gordon, the newly appointed British governor general of Sudan, then dismantled slave markets and detained traders in a bid to quickly fulfil the terms of the convention. This led to a crisis of the Sudanese economy which was largely based on slavery. Additionally, the Sudanese soon determined that the campaign, developed by European Christians, was against Islamic traditions and principles. By 1879, the Sudanese had pushed back fiercely against Gordon’s campaign and soon, the Mahdist movement was born.

Muhammad Ahmad ibn al-Sayyid Abd Allah, later dubbed al Mahdi (Arabic for “Right-Guided one”), created a theocratic state in Sudan and founded the Mahdist movement. In 1880, Muhammad Ahmad travelled throughout the countryside of Sudan and found that a great deal of Sudanese people held a deep contempt for the regime. This was owing to various reasons such as the attempt to abolish slavery, fiscal injustices, being harshly flogged as punishment for late tax payments, the occupancy of non-Muslim Europeans who consumed a lot of alcohol and so on. On the other hand, Ahmad’s personal contempt for the ruling class was based on his deep religious beliefs which he believed they stood against.

In 1881, he told his disciples that he was instructed by God to purify Islam and rid the land of all governments that defiled it. His self-proclaimed title “al Mahdi” was a pointer to his divine appointment to restore traditional Islam. He was able to mobilise his fellow discontented Sudanese into a seemingly invincible military movement. Within less than four years, al Mahdi had led them to conquer most of the former Egyptian territory, and capture sophisticated military supplies and fortunes in booty. By 1883, his ansar (helpers) had thrashed three Egyptians armies – the last of which comprised 8,000 men – deployed against them.

A year later, the Mahdist army was making moves to conquer Khartoum, the seat of the Egyptian government in Sudan. Consequently, Gordon was ordered back to Sudan to see to the evacuation of Egyptians from Khartoum. Instead, Gordon chose to put together a defence against the Mahdi and his troops. His hope was that they would conquer them and prevent their impending advancement into Egypt. On March 13, 1884, the Mahdi’s troops besieged Khartoum. On January 26, 1885, 50,000 Mahdists stormed the city, killing Gordon and the remaining 7,000 defenders of the city, Khartoum fell. Soon enough, Anglo-Egyptian power in Sudan had essentially been obliterated.

The Anglo-Egyptian Reconquest of Sudan

On June 22, 1885, the Mahdi died at Omdurman which he had made the capital of the Mahdist state. The rule of the state then fell to his khalifah, Abd Allah who was even more ruthless in his quest to expand. Under him, the Mahdists were able to conquer some of Ethiopia. However, they stood powerless against the well-supplied British-backed armies in Egypt. In 1889, the Egyptian army defeated 6,000 Mahdists who were ordered into Egypt. In the years that followed, Anglo-Egyptian forces, and at times Italian and Belgian troops, had defeated and expelled Mahdist forces. By 1896, a significant portion of northern Sudan was back under Egyptian rule.

In 1898, a British brigade was deployed to join Anglo-Egyptian forces at the front line, south of Abu Hammad in Sudan. On April 8, the Anglo-Egyptian forces, led by Horatio Herbert Kitchener, destroyed the Mahdist defences at the Battle at Atbara. About 3,000 Mahdist men were killed while hundreds were captured. In contrast, their opponents only had 80 killed and 470 injured. Now that a significant proportion of the Mahdist army had been annihilated, it was time for Kitchener to make his way to Omdurman.

On August 24, an Anglo-Egyptian force comprising 26,000 men was put together. This force had a heavy British involvement, and even included the British 21st Lancers of which Winston Churchill was part. The force also had a number of Sudanese loyalists. The Mahdists forces were about twice their number at over 40,000, but the Anglo-Egyptian force had the advantage of heavy artillery, Royal Engineers, sophisticated machinery, and a high level of training. An Arab force assisted in ensuring there was no opposition on the east bank, while the Anglo-Egyptian army marched freely along the west bank. On September 1, British gunboats shot at the Mahdist forts, thereby breaching the wall of Omdurman.

On the morning of September 2, the Mahdists launched a frontal attack on the Anglo-Egyptian camp, but were no match for the rapid-fire artillery, machine guns and mass rifled fire their opponents responded with. That same day, Kitchener would inflict even more heavy losses on the Mahdists. The Anglo-Egyptian army did record some losses though. While they were separate from the main Anglo-Egyptian army, the 21st lancers were ambushed by some 2,000 Mahdist infantry. They managed to escape, but with one-fifth of them wounded or killed.

Nonetheless, Kitchener and his troops scored major victories in Omdurman and Sudan at large. The Black Flag Division of Abd Allah’s troops were captured and sent to Queen Victoria in London, dozens of European captives of Abd Allah were released, and Abd Allah and what was left of his army fled Kordofan. On September 4, the British and Egyptian flags were hoisted in Khartoum and a tribute ceremony was held near the location of Gordon’s death.

The Aftermath and Perception of the Battle

At the end of the battle, Mahdists had suffered losses of 11,000 deaths, 16,000 wounded and 5,000 captured – a stark contrast to the merely 500 Anglo-Egyptian army casualties. The corollary of the battle was the virtual obliteration of Mahdism in Sudan, and the concretisation of British dominance there. In 1899, Sudan essentially became a British protectorate. The British would then spend the year solidifying their rule in Sudan, and extinguishing what was left of the Mahdist movement. In November of that year, Sir Reginald Wingate – the then governor general of Sudan – deployed 3,700 men to Kordofan to neutralise Abd Allah and his remaining army. On November 24, 1899, Abd Allah died in battle. Seeking to avenge Gordon’s death over a decade earlier, Kitchener exhumed Mahdi’s body, pulled out his fingernails and bombed his tomb.

Historians have widely referred to the events of September 2, 1998 as a massacre rather than a battle. Some opine that proper consideration of the atrocities committed by the British against the Mahdists would hamper the whitewashing of the British colonization in Africa, in comparison with its European counterparts. During the battle, Kitchener encouraged his troops to remember Gordon – using vengeance as fuel for violence. Troops were advised to starve out the Mahdists, villages, food stores and towns were destroyed, and surrendering Mahdists were treated in a despicable manner.

Oyindamola Depo Oyedokun

Oyindamola Depo Oyedokun is an avid reader and lover of knowledge, of most kinds. When she's not reading random stuff on the internet, you'll find her putting pen to paper, or finger to keyboard.

follow me :

Leave a Comment

Sign in or become a Africa Rebirth member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.

Related News

Congo’s Unfinished Revolution: Patrice Lumumba and the Struggle for Sovereignty

Jun 01, 2025

When Oil Was Worth More Than Lives: Britain’s Role in the Biafran War

May 31, 2025

How Mozambique Broke Free from 500 Years of Portuguese Rule

May 30, 2025