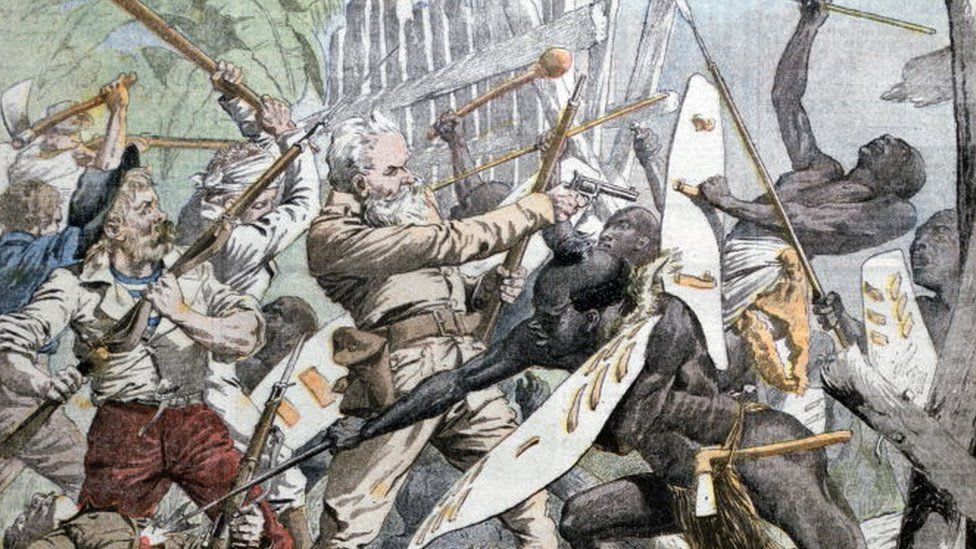

The superiority of a revolutionary ideology rooted in African spirituality to challenge European colonial hegemony in Tanganyika threw Germans off balance. While this religious movement - with its incendiary potency later watered down by 'tribal organizations' - swept across the south-eastern region of Tanganyika, German colonial officials derided it as 'witchcraft’.

German colonial authorities, spurred by the Empire, quelled the borderline organic rebellion ruthlessly to the extent that narratives for whether this qualifies as genocide have proliferated in academic and political realms.

At its core, the Maji Maji Rebellion started as a 'peasant revolt' but transformed into an uprising that enveloped most parts of the colony. It brought together different ethnic groups that had previously shared no ethnic links. The rebellion was centered on sheer prophetic charisma that presented water medicine - the maji - as the sole spiritual rallying point to coalesce different ethnic groups in Tanganyika to fight the common menace of German colonial repression.

Maji Maji as the Inspiration for Post-Colonial Tanzania

The new nation-state of Tanzania came into being in 1961 upon weaning itself from British colonialism. Julius Nyerere, a principled leader, was tasked with the prerogative of lifting this post-colonial polity towards new heights of inimitable social cohesion, inclusiveness, self-sufficiency, and holistic emancipation. Such a nationalist task was a delicate one; and a new nationalist narrative was brought up. Nyerere repeatedly referred to the Maji Maji as the inspiration for local African solutions for African problems, in the battle against neocolonialism.

Colonial narratives in Germany and Britain dominated how the Maji Maji story was told. However, Tanzania's higher learning institutions – chiefly the University of Dar es Salaam through Gilbert Gwassa and John Iliffe, with the able support of Terence Ranger later assumed the public mandate of developing groundbreaking research that sought to portray the Maji Maji as an intrinsically African rebellion that transcended ethnic differences through the unifying force of revolutionary ideology supported by interethnic unity.

Germany’s Exploitative Rule in Tanzania

For all the contradictions reigning supreme in the 1880s and 1890s among Europe's industrialized powers - the harbingers of modern capitalism in its rapacious 21st century forms - carving out Africa's territories for their aggrandizement certainly constitutes one of the greatest moral affronts humanity has witnessed.

Germany had been among those voraciously interested in acquiring colonial possessions for unbridled private profit - following in the United Kingdom's mould. Carl Peters in 1884 developed a relentless interest in establishing an East African colony when he first set foot in Zanzibar.

He made further inroads into the interior; first into mainland Tanganyika and later Uganda, leaving a devastating trail of callous brutality. He was backed by the German East African Company as well as the German Colonization Society which he founded. Peters negotiated deceptive treaties with local leaders without official approval from the German Empire's government, and the brutality meted to local populations under his watch were inexorably remorseless.

The merciless brutality elicited frenzied outcry in the German press, and in 1890 the German government took over the colonies from Carl Peters and several other traders/merchants - an exercise undertaken to orchestrate private profits became heavily subsidized by the state.

Early Attempts by Tanzanians to Repel Colonialism

European encroachment and effective establishment of settler regimes was not taken lightly by the people in Tanzania. Mounting victorious resistance proved an onerous task for local populations owing to scant and disfigured co-ordination among different ethnic groups. Nonetheless, the reality of a mass movement never seemed a distant prospect.

Some groups staged valiant but futile resistance against the German colonial machine. As put by Iliffe, between 1891 to 1893, the Mbunga clashed with German forces several times and different groups in the Kilwa hinterland had participated in Hasan bin Omari's resistance of 1894-95.

How Germany Ruled the Colony of German East Africa

German East Africa transposed the African peasant way of life with cotton-farming. This vicious commercial agricultural enterprise has been pointed out by several historians as the origin of the rebellion's outbreak in July 1905. Such colonial repression via cotton-farming propelled the initial outbreak of the rebellion before it assumed its 'supra-ethnic' identity.

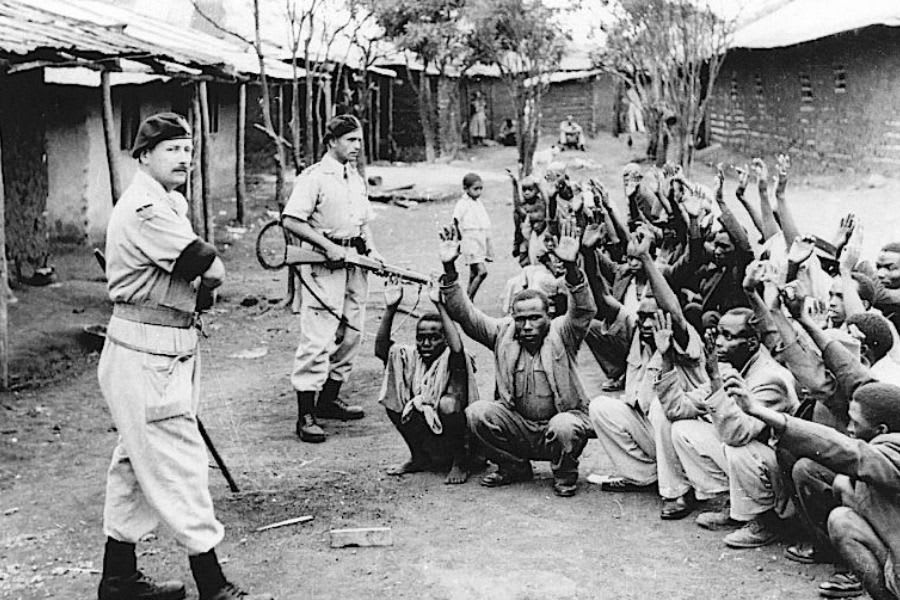

When the Germans established their rather shaky colonial rule over German East Africa, with imperial aspirations to feed the global consumer market as other colonial behemoths such as the French and the British did, they ran their colonies via indirect rule. This meant the imposition of the cruel Askari(local African and Arab soldiers on Germany's side) and akidas (Arabs and local Africans chosen as district administrators). These alien agents supervised the collection of taxes with unmatched repression.

A money-driven economy soon enveloped Tanganyika and much of German East Africa - forced labour to coerce Africans into the payment of taxes was prevalent. Heavy taxation was imposed in 1898 to fund the construction of roads and other settler infrastructure. It was in 1902 when Peters ordered the growing of cotton as a cash crop for export, signalling the loss of fertile arable land for the Tanganyikan peasants.

A hut tax was soon supplanted with the head tax, enabled by the brutality of the Askari and akidas. This alienation, grounded in cotton farming to raise taxes for the colony's income and profits, necessitated revolt.

The disruption in the peasantry subsistence ways of life to serve global consumerist demand while their [peasants] poverty knew no bounds had to be blind to ethnic differences. Tanganyikans were only compensated through the whippings of the akidas.

Colonial Repression and Interethnic Unity as the Sources of the Maji Maji Rebellion

The revolution's provenance, as pointed by Iliffe, can be sourced to frustration and angst following the disruption of their livelihoods - a peasant revolt. Such a rebellion transcended peasant grievances to embody the soul and ethos of a once ethnically-divergent people to fight colonialism.

Through Kinjikitile Ngwale, a fiery charismatic prophetic leader and minister Kolelobelief system, the rebels used the maji - medicinal water or sacred water - as a clarion call for ideological religiosity as a weapon for interethnic solidarity. Kinjikitile emphatically declared that he had been sent for such a 'holy war' through possession by a snake spirit called 'hongo' - subordinate to Bokero (the chief deity along the Rufiji Valley).

At the instigation of Kinjikitile,who first led the Maji Maji, different tribes were able to spread the maji message via 'Njqiywila' or secret messages. Kinjikitile claimed that the maji could repel German bullets - specifically, that the bullets would turn into water - and as such Tanganyikan warriors had nothing to fear.

Given the historical context of the Maji Maji Rebellion, what happened as the revolt broke was first grounded in the unpopularity of the cotton scheme. Quoting Iliffe, "cotton was everywhere an object of attack" as the revolt first broke out from July to August 1905 in the Matumbi Hills of the Rufiji Valley.

With concrete and unwavering conviction in the religious superiority of the medicine-water, warriors of different tribes coalesced under the unifying symbols of millet stalks around their heads, arrows, and spears doused with the sacred water, sometimes laced with poison. Though this was poor weaponry in the face of Germany's advanced weapons (they had machine guns that massacred up to 75,000 Maji Maji warriors).

On July 31, 1905, alongside the deliberate destruction of cotton plants, the first warriors of the rebellion began to move against the Germans. At first, they attacked only small German outposts such as at Samanga. Kinjikitile was subsequently hanged for treason but prior his demise he charismatically proclaimed that the revolution had spread to all other parts of the colony.

What started as a peasant protest movement against a distasteful cotton plantation scheme - aggravated by the cruelties of the Askari and akida - soon transcended the confines of the Rufiji Valley to other parts of the colony. Ngindo tribesmen speared to death five missionaries who were on a safari on August 14, 1905 - including Bishop Spiss, the Roman Catholic Bishop of Dar es Salaam.

The Maji Maji Rebellion assumed an ideological content from prophetic religious leaders and with this the revolt, it gave a certain, though arguable, degree of unity among diverse people.

With its spiritual outlook, the revolt was also embraced as a movement to eradicate sorcery. Later on in the struggle, rebels maximized tribal organization, a phenomenon that Iliffe asserts was contrary to the unity-creating purpose of the first Maji Maji rebels. He argued that "the rebellion demonstrated tension between ideology, political and cultural reality which is characteristic of mass movements, including later nationalist movements."

The Ruthless Quashing of the Maji Maji Rebellion

Kaiser Wilhelm sent two cruisers with a thousand German soldiers to quell the rebellion. The reinforcements sent by the Emperor destroyed villages, crops, and other food sources used by the rebels as well as making efficient use of their firepower to break up any attacks the rebels might launch. By 1907, the rebellion had been quashed, but at great loss of human life. This was also due to the famine suffered by Tanganyikans, deliberately imposed on them by the Germans.

This mass starvation decimated entire populations particularly in the south where the rebellion had originated. Famine was chosen as a weapon of war to flush out the remaining rebels following the violent military conquests. Captain Wangenheim, one of Germany's colonial war leaders, said "Only hunger and want can bring about a final submission. Military actions alone will remain more or less a drop in the ocean." When the rebellion ended, Germany suffered a handful of casualties - 15 European soldiers and 389 Askari/African fighters died; while on the other hand, the number of dead Africans reached 250,000 to 300,000.

From the 1950s when Tanzanians were pressing for independence, nationalist narratives of the Maji Maji possessing a uniquely African character free from external influences abounded. This signified a defence of African liberation as well as giving legitimacy to the Tanganyikan nation that was soon to become Tanzania in 1961.

The Contested Historiography of the Maji Maji Rebellion

When Tanzania got independence, this discourse gained fresh momentum - with historical luminaries Iliffe and Gwassa largely contributing towards the re-writing of such an important piece of history. Much of the Maji Maji's historiography reflected European biases which attributed the revolt to superstition, sorcery, colonial maladministration, and British justifications to highlight its colonial supremacy over Germany.

New attempts to correct this biased literature asserted that colonial repression was the source of the revolution and medicinal water - maji - was instrumental in unifying diverse ethnic groups for one common goal. The maji symbolized a "unintary ideology" which according to Gwassa cut across and discouraged clan and ethnic boundaries. It is in this context that Gwassa remarked that the Maji Maji rebellion is the "national epic of Tanzania".

Such nationalist views, which are vindicated by the context of building a unified post-colonial African nation unencumbered by ethnic/tribal differences, have been consistently challenged to produce more nuanced analysis.

Other historical observers note that the Maji Maji did not necessarily reflect a unified African spirituality that birthed a universal and homogenous ideology - they attribute the participation of other ethnic groups to self-serving interests. For instance, the Ngoni, a Ndwandwe group that fled north from southern Africa entered the war to re-establish its waning influence among Tanganyikan peoples.

Internal power struggles spurred individual motivations in joining the war. Accounts of the rebels coercing sections of the local ethnic groups into joining the war have surfaced, notably in the Msongozi and Kilosa areas.

The broader influences of Christianity (brought by colonial missionaries) and Islam (a mainstay in the region because of Arab traders) – Abrahamic sources – have been attributed towards influencing the Maji Maji to take its spirititual outlook, thus removing African indigenous spirituality as the sole force behind the rebellion.

Why the Maji Maji Rebellion is Important in Present-day Africa

Regardless of such contradictions in the historiography of the Maji Maji, the salient point to note is that it was a revolt rooted in deep conviction, courage, patriotism, and a desire for interethnic unity. This inspired the nationalist struggles for independence and continued to shape the trajectory of Tanzania as a new nation under Nyerere.

In the contemporary, the Maji Maji Rebellion is important because it signifies that to achieve the holistic emancipation of African peoples, unity is indispensable - ethnic differences should be put aside in fighting the common enemy afflicting Africans, which is neocolonialism.